In the 70s when I was a kid, summer afternoon naps were obligatory. And unlike my siblings who faked sleep, I dozed off easily, knowing that when I woke up, mother would send me to buy cassava pudding for merienda.

Clutching a one-peso bill, I would run to this old garage in the corner two blocks away that the sixtyish Iya Inggin had transformed into a makeshift work station-cum-snack bar. On one side, close to the wall of wooden sticks, were wrought iron chairs and two enamel tables. On the opposite side was the cooking area where firewood crackled under a vat steamer and a large wok. By the door was a table stacked with layers of pudding individually packed in cellophane and wrapped in Manila paper twisted around the edge in such a way that they looked like French empanadas.

Other than it being spotlessly clean, it wasn't a pretty structure; it didn’t even have a window and a floor under its nipa roof. But that people trooped to it like ants to sugar was a sweet testament to the sheer magic by which she prepared her concoction like no other.

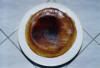

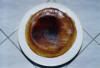

I liked my pudding fresh from the mould, but only because I liked watching Iya Inggin fish one from a large planggana and trace the shape of the circular mould with the handle of a plastic fork before flipping the pudding into the cellophane with the caramelized side facing up. Then from a bowl using a golden spoon, she would scoop the arnibal---a deep brown syrupy topping made from the purest coconut milk and brown sugar---and twirl it into a small cellophane with an amazing sleight of wrinkly but dirt-free hand.

At home, before my parents and siblings each holding a fork and a saucer, I would transfer the pudding to a plate, section it with a knife, and pour and spread the arnibal on top. Then to the sound of metal clinking against china we’d devour it by munching the sweet, soft, sticky mixture, making it linger in our mouth before letting it slide down our throat. For always, it was lip licking good!

Pudding making involves an elaborate process that requires attention to details. The cassava must be fresh and average-sized for the pudding not to taste bitter and grainy. Meticulously peeled, the cassava must be washed five times in running water before it is grated. Pudding makers---if I may digress—now go to commercial electric grinders, but in the 70s when our town had yet no electricity, Iya Inggin grated the cassava on a punctured galvanized sheet with the Camay girl held at both sides by sticks. And every now and then---or so they said---Iya Inggin would deliberately scrape her hand and let the blood seep into the mixture, both to improve the pudding’s taste and to hook forever her customers!

The grated cassava is put inside a katsa flour sack and wrung dry. The process is repeated thrice for better pudding texture. In fact Iya Inggin had a contraption made from under whose fulcrum she placed the grated cassava before she and her housemate (she was a widow) mounted the wooden plank running across it like a see-saw.

The sapped cassava meat is then transferred to a large bowl where it is manually combed for pulps and crumbs. Mixed with other ingredients like sugar, coconut milk and vanilla, the hodgepodge is then poured into an 8-inch, brown sugar-sprinkled mould and steamed. When it turns opaque---the tell tale sign that it’s already done---the pudding is placed on a basin that contains just enough water to cool it without soaking.

Cooking pudding is admittedly elementary; but cooking the arnibal is tricky: too thin and it drips and messes up the pudding’s presentation; too thick and it can’t be spread. A pudding maker told me that the best way to cook arnibal is to stir it constantly over low fire until the right consistency is attained, that is, when it doesn’t trickle if twirled with a spoon.

It’s an immutable fact in our town of Tago in Surigao del Sur that only Iya Inggin could whip up a perfect arnibal to go with her perfect pudding. Patrician and a member of Tago’s beautiful elite, she reigned supreme, thus earning from me the title, the pudding icon!

There are at present six pudding makers in Tago. But since Iya Inggin’s death in 1997 when she brought her recipe and technique to the grave, I haven’t eaten something as heavenly!

Pudding addicts continue to troop to Tago like devotees. And they swear that it’s best to chill first the pudding before eating it. I agree, but still I like mine fresh from the mould. If only for the sweet memory.