bad news, good news!

first, the bad news: THIS BLOG IS DEAD!

now, the good news: I HAVE A NEW BLOG!

if you're interested, catch me at http://kspy65.blogspot.com.

just a denegerate vagary of thought.... lucid interval is that space of time between two fits of insanity, during which a person is completely restored to the perfect enjoyment of reason upon which the mind was previously cognizant. that, in a perfect way, is the essence of this blog. and because lucid interval comes to the mental pervert few and far between, this blog also does.

first, the bad news: THIS BLOG IS DEAD!

As a child, I always believed that crabs would never run out in Tago, my hometown in Surigao del Sur, even if they were peddled in the streets morning, noon and night.

LOOKING AT THE STARS

I’ve always loved movies. And I'm lucky to have parents---God bless their souls---who considered movies as a medium of learning.

In the 70s, waking up early was a pleasure because it meant joining Papa to buy either carabeef or pork in the market, a rickety building that stood where the present terminal is. The same building would press a woman to death when it collapsed from strong winds in 1978.

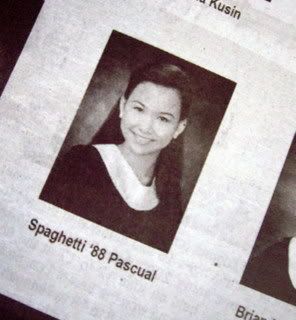

-(Note: On my return flight from Manila to Davao last 2 June 2007, I saw this one-page spread congratulating the 25 Journalism Graduates of the Manila Times. The name of one of the graduates struck me and became my muse for this first attempt at flash fiction. Word count is placed at 690.)

“Spaghetti’s here,” says the man outside.

In your mind you see her lay on the narrow table the food that she always brings. Until now it eludes you why she does this when she knows you have stopped eating it since the incident. Perhaps it's her way of letting you exorcise your demon.

You met her father on this generation’s luckiest day: 8-8-88! You were at your favorite restaurant when he asked if he could join you. You were actually done but good manners aside, you didn’t want to foist bad luck on him by leaving just when he was about to eat.

His tray carried only spaghetti.

Outside, the Dragon Dance that you came to watch had begun. But then he spoke and time lost its sense.

Soon after that, you dated. And because you hated spaghetti, he made you learn to love it. A year later, you named your daughter after it.

“You hear me? Spaghetti’s waiting for you,” the man outside says.

You glance at the cracked mirror one last time, tuck a wisp of gray hair behind your ear, and head for the hall.

She’s a sight in a white sundress and you wonder if she would wear white to her debut in September. Or if she would finally wear---after a long while---the smile that reminds you of him.

As you sit, she opens a Tupperware that contains pasta and another that contains the sauce. Something grumbles in the pit of your stomach.

She fills two plates with spaghetti. “Here,” she pushes one towards you.

You pick up the fork, jab the spaghetti, and twist it. Then as always, you stop and close your eyes: The knife felt cold in your hand as you watched furtively in the dark. As orgasm gripped him, you raised the knife. But then he turned as though he knew, and the knife brushed past his shoulder, into the mouth of the girl under him.

He rolled out of bed. But the sheets tangled at his feet and he fell to the floor. You lunged and straddled him, and then you stabbed him everywhere, twisting the knife each time. Blood squirted on your face but your hand went up and down until you could no longer see.

“Ma, are you alright?”

You open your eyes and see that your knuckles have turned white from gripping the fork.

“It’s been three years," she says, reaching for your hand.

You look at her. And all you can see is the scar on her lips.

Fully Booked, at the Mall of Asia, is separated by a road from SM Department Store. When I entered it, there was but one customer at the corner stand, slyly tearing the cellophane that sealed The Buzz magazine.